The Flaw In Banning Billionaires

I recently watched the excellent video “The Political Spectrum Is a Myth” by Andrés Acevedo on the YouTube channel The Market Exit, and I absolutely loved it. That should not be surprising given my book that proposes an inclusive party system that debunks the unidimensional political spectrum. I found the ideas compelling and strongly agreed with its arguments, which immediately made me want to watch more of his work. As a result, I went on to watch another one of his videos, “Why Billionaires Should Be Illegal”, which I found just as engaging.

Billionaires, Power, and Democracy

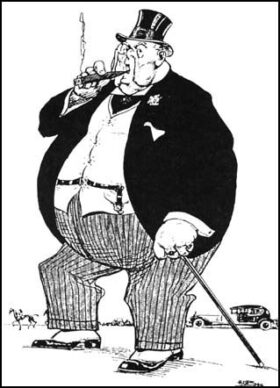

One of Andrés’s central arguments for making billionaires illegal is that extreme wealth poses a serious threat to both capitalism and democracy — and this is a point I strongly agree with. Western societies have improved precisely because capitalism and democracy decentralize power. From that perspective, extreme wealth is worrying because it signals an extreme concentration of power.

I deliberately use the word “signals” rather than “creates”. In our current capitalist system, where billionaires are legal, economic power is relatively transparent: it can often be approximated by a single number — someone’s net worth. In a society where billionaires are outlawed, or more broadly where property rights are weakened, economic power becomes far more opaque. This is a clear example of Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, it stops being a good measure. Knowing who the billionaires are is actually useful. Once billionaires are prohibited, those who hold the most economic power will simply find ways to hide or disguise it, making power less visible and less accountable. We can already see some of that, e.g. Bill gates lost a lot of wealth when creating his foundation, but he did not lose as much of his economic power.

Moreover, strong property rights are essential for maintaining a democracy in which economic power remains sufficiently independent from political power. Xi Jinping may well be the most economically powerful individual in the world — not because of personal wealth, but because China’s system does not meaningfully protect property rights. As a result, economic power is overwhelmingly concentrated in the hands of the political elite. Outlawing billionaires risks producing a similar outcome: shifting economic power away from private actors and toward political elites, thereby weakening our democracies rather than strengthening them.

The Naivety of Banning Billionaires

The prohibition of billionaires is in my opinion a clear example of naïve interventionism. It tries to fix a problem in a complex system by targeting the symptoms, not the causes. In my book, I discuss how political parties are currently still centralising power too much. A naïve interventionist approach might be to forbid any party from having a majority and thereby preventing a single party from having too much power. But that would not solve the underlying problems of our current political model or give us much more understanding for why things go wrong in the first place. Similarly, when we buy something, we vote in the economic domain and hence give more economic power to those that made good economic decisions within the legal framework.

So should we simply do nothing about billionaires? Absolutely not. Instead, we should focus on the root causes that allow extreme wealth to emerge and on the specific ways it threatens decentralization. For example:

- Weaken intellectual property rights (which are not genuine property rights in the first place). Intellectual property by definition creates monopolies and therefore concentrates economic power. Unlike real property, IP does not protect against theft but against copying. So by weakening intellectual property, we do not transfer power to the state (and therefore political elite), but to the masses directly.

- Introduce a progressive tax on political donations. Small donations should be tax-deductible to encourage broad participation, while large donations should be heavily taxed to prevent outsized political influence. This will strengthen the separation between political and economic power.